After writing a great deal about my playtest experience, I realize it would be more useful if I broke it up into different posts. This post addresses my experience with creating a character. Future posts will address other aspects of my playtest experience.

Ability Scores: Cast the Dice

The first step in creating a character is rolling dice to determine ability scores. The default rule for D&D Next, at least for now, is to roll 4d6 and drop the lowest. The rules provide both a point buy method and a "default array" for those not interested in entrusting a campaign-long decision to a single roll of dice. I find it puzzling that the default would be random rolling (as this is generally prohibited in organized play anyway) but at least they made it clear point buy methods were acceptable.

|

| Go ahead. Trust the rest of the game to the a few simple dice rolls. What's the worst that could happen? |

The Section of the Great Race

I do not have a whole lot to say about the race section. Although there are only the "standard" races available at this time, the Wizards of Renton have tried to present options for each race by dividing certain abilities and bonuses across separate "sub-races." Hill dwarves are better at different things than Mountain dwarves but they both share some features as well that Halflings and Elves do not have. It is an interesting way to do it and I wonder if they will continue to do this as more races are added to the collection.

There are a few strange issues that are likely to be fixed after a few iterations. For example, where previous editions gave certain races certain proficiencies to weapons, this current edition only gives a bonus to damage if the character already has proficiency. The net result is that non-Fighters tend to gain no benefit from the racial weapon training while Fighters get a statistical +1 to damage. I suspect that will be changed in future iterations. But the issues present in this version of the playtest seem minor. Unlike my pass with the ability score system, nothing here seemed to irk me.

Choose Your Character!

Choosing a class was a difficult endeavor for me. As of the current playtest document, there are only five classes available. This version of the playtest materials had the "standard" D&D classes of Fighter, Rogue, Cleric, and Wizard. Although I realize that these are iconic classes in the game, I wonder why they did not focus more on a set of classes with fundamentally different game mechanics. As I see it, There were really only two classes to choose from here: the Maneuver class and the Gygaxian Caster. The biggest difference between the Cleric and Wizard was spell selection and weapon/armor proficiencies, so it does make me wonder why those two classes would not fall under one class, leaving an opening for a class with a fundamentally different mechanic (Sorcerer? Psionic?). But, I digress.

|

| "Choose your Character!" This is roughly how I felt when I started the Character Creation process. |

|

| Monk was my natural guess for "next class to include" as well. Right? |

Some of you may look at my previous comment and think I am a bit crazy. "But Monks don't have the weapon and armor proficiencies that a Fighter has!" That's true, but I noticed that at our table the Monk rolled a d6 for damage (instead of d10 or d12) and had an Armor Class that was one lower than the Fighter. As I saw it, the "proficiencies or powers" mattered less than how it played at the table. Fighters had a larger damage die and slightly higher Armor Class. Monks, in exchange, got a quasi-magical power. "Guy who fights with Weapons" did not seem that much different to me than "Guy who fights with fists."

Despite only participating in a "one off" playtest session, I still had the urge to create a character that was more than just a named piece of equipment (like "Jax the Fighter"). Unfortunately, every interesting idea I had did not fit within the classes and races provided by the playtest packet without modification. Sometimes serious modification. My first impression was that this was a game that wanted you to conform to it and not a game that would conform to you. This was not surprising, though. Classically, D&D always starts with a limited set of options and gains more options, allowing more freedom in character creation, as the edition progress. I think my frustration came from the fact that I am used to having a wide pallet to work with (with Fourth Edition), so the restricted selection of choices is frustrating. Either way, I would have to find something to play.

Where Beer and D&D Collide

Frustrated, I started to look through the packet for some feature to inspire me. I decided that as none of the other players had made a Monk, it would be appropriate for me to test out. That being said, I'm not one for the typical Quasi-Asian monk. It usually felt surprisingly out of place in an otherwise very Tolkien setting. I tried to think how I could torque the Monk class to feel more in place in a standard fantasy setting. Somehow, I immediately thought of a Franciscan Monk with a surprisingly violent streak. Between prayer and brewing, this Monk would take time out of his day to smash in the face of villainous monsters. From that idea, Brother Sheltem of the Monastic Order of Helm was born.

|

| The Monastic Order of Helm is best known for brewing the legendary beverage known as Helmsbier. |

Alignment: The Point Where the Game Tells Me How to Act

Back when I played Dungeons & Dragons in the early 1990s, I remember getting really wrapped up in the idea of "Alignment." It did not take long for me to start to have issues with the two axis alignment system. Ideologies like "Lawful Evil" or "Neutral Good" began to make less and less sense to me as I got older and tried to decipher what it meant for something to be good or evil. Over time, I would come to disregard it entirely, leaving it out of games as it appeared. The Fourth Edition of Dungeons & Dragons had a relatively light treatment of it so it was not hard for me to not pay attention to it. Since the new D&D Next playtest arrived on the scene, the old alignment system is back!

This bothered me a little bit at first but it did not take much for me to realize I did not care all that much. I would ignore it, just as I had before. What did bother me, though, was the alignment restrictions attached to the new Monk class. It was not a new restriction, being a mirror of previous editions, but it still bothered me. Monks had to be lawful. They could be lawful evil, but chaotic good was off the table. As I thought about it, the whole thing felt like a missed opportunity.

|

| Chaotic "Monk" vs. Lawful "Monk" Seriously? Nobody thought of this before me? |

Skills and Things

|

| Dungeoneering. Covering every skill adventurers need since 2008. |

But I don't.

Despite being very much against the "big umbrella" skills of Fourth Edition at first, I've actually grown to like them quite a bit because they allow players to accomplish similar tasks using different skills. Need to climb a cliff? I've had players make arguments for Athletics, Nature, Acrobatics, and Dungeoneering. Need to smooth talk the head of the Wizard's Guild? Try Diplomacy, Bluff, Arcana, or Streetwise. So, when I see a skill like "Rope Use" or "Spot," I feel that although there are a lot more skills to choose from, they are all a lot less useful. That being said, I would have to see how these seven or eight skills worked out in actual play before I made any judgment on their effectiveness.

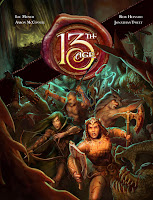

With 13th Age due to be released in the next few months, I think about how they utilize Backgrounds to fill the space of Skills instead of specific named skills. To a certain extent, they took the generalization of skills seen in 4E and moved it to the realm of character background. This makes a simple skill roll an exercise in role-playing and collaborative storytelling as player's explain why a Centurion of the 501st Legion would have experience crocheting. I have grown to really like that method, so the fact that D&D Next has gone back to extremely specific, discrete skills is disheartening, to say the least. But, as I keep reminding myself, time will tell.

A Fully Loaded Killing Machine

The playtest rules have rules for purchasing equipment. Anybody who has read my stance on tracking things like character equipment will know that I really do not care at all about it. There was a big list of weapons. I cannot imagine why the list needed to be that big. Furthermore, as a Monk, I did not really care about that list of weapons. To that end, I cannot say a whole lot about equipment in D&D Next as it applies to character creation.

|

| Equipment! There's nothing more thrilling in a role-playing game than worrying about how many feet of rope you remembered to bring. |

I am surprised that they so quickly disregarded the weapons rules from Gamma World, where the player would choose a basic category and create what weapon they had from that category. I thought the guy who chose a heavy, two-handed ranged weapon that was a Microwave that shot radiation at people was pretty great. I suppose that is a style for a different kind of game.

Creating Characters: Conclusion

Right now, character creation in D&D Next feels very limited. Ideally, most of that will change over time. On the good side, character creation was relatively simple and I was able to finish it in less than a half hour. To a great extent, I feel like the quickness had a lot to do with the lack of options and less with any sort of clever design. As more races, classes, backgrounds, and specialities are added, I suspect character creation will begin to slow down a bit.

As I completed my character, I started to feel a little skeptical about the lack of options my character had. It seemed like he had one or two things to do in battle and a strange arrangement of skills. However, that concern mostly came from my perspective as a Fourth Edition player. I would reserve my judgment until I witnessed how it all panned out in play.