Phantasy Warrior Advance: Please Pay All Late Fees In Advance

This goes back to my original application to take the LSAT, but it's true of just about everything nowadays. I feel like the idea of the late fee to apply for something must have been conceived of one day by some guy. Other people heard about it and thought, "Oh, crap! That's a great idea!" Pretty soon, everybody is doing it, often for things that do not even matter.

More frustrating than the late fee, though, is the ridiculous idea of itemized "fees." I often see applications that have five or six itemized fees, singled out one by one as if somehow it made them more palatable when delivered in pieces. The worst is when you see an "application fee" but then you see three or four more fees that sound like they should clearly be part of the application process but somehow warrant separate billing. "Processing fee" is my favorite. Did you intend to accept the application but not process it, hence the need for a separate processing fee? It never made sense to me.

Unfortunately, it's pervasive. Everybody seems to do this nowadays. I guess there is no use fighting it. Of course, if you are a young would-be hero, what do you do if you cannot afford to pay? We will see...

Seattle's (self-proclaimed) Capitol Hill Gamer Viceroy writes about Dungeons & Dragons, board games, card games, and more.

Friday, June 29, 2012

Thursday, June 28, 2012

Dungeons & Dragons: Ace Attorney (Part 1)

As a gamer of many stripes, I have played a lot of different games. I have been doing so for the better part of thirty years. As I have been creating characters for Dungeons & Dragons: Encounters, I have tried to think of iconic, interesting, or just damn awesome figures from games that deserve representation within the framework. Sometimes, I come up with one, like Leisure Suit Larry, and I find a way to work it into the D&D framework in a way that seems to fit. In other situations, I sit for months trying to find a way to get it to work, often to no avail. Occasionally, though, months and months of sitting manifests in ways I never would have imagined.

I started playing Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney before going to law school. I used to always insist that I was "training" for my big days as a lofty attorney. I would never have believed that somebody could make a classic adventure game out of comical parody courtroom drama, but they did. The characters were ridiculous, entertaining, and all around awesome. As I fell knee deep into Dungeons & Dragons character development, I felt like I wanted to find a way to capture some of those characters into the D&D game.

The challenge proved harder than I anticipated. Making Phoenix Wright proved more difficult than I had imagined. What I wanted was some sort of psychic, ranged defender. I wanted to find a character that felt like he did what Phoenix Wright did so the re-skinning would be simple. After months of struggle, I gave up. But, in that time, something else came to mind. There was a character, easily captured within the game rules, that I could make. From that, I began to work.

When I thought "Miles Edgeworth," I immediately went to "Infernal Pact Warlock." After a little look at that, I thought that I could do better. I wanted something that would feel like it came out of the game. Setting people on fire did not capture the Miles Edgeworth I had hoped for. As I flipped through the Warlock options, though, I came across the Dark Pact and the Sorcerer-King Pact, both options that could be easily adapted to serve as my favorite prosecutor. [Author's Note: I did spend two years working at a prosecutor's office and, although I do adore the character Miles Edgeworth, I actually seriously question his effectiveness as a prosecutor.] After toying with both, the Sorcerer-King Pact seemed like a simpler option for new players and an easier way to capture it into the "Edgeworth" character.

Warlock aficionados will likely detect that I have broken up the Warlock's Curse power into *four* different abilities on the card. Honestly, that was done to make the Warlock's Curse power more digestible for new players. It is a huge block of text that is quite confusing for players new and old. In this format, I had hoped to present it in a way that was functional and easy to understand. Of course, as I had chosen the Sorcerer-King Pact, I had to introduce a way to track "fell might." It did not take long to develop and system, though, and from that Miles Edgeworth was born into the world of Dungeons & Dragons.

[Note: I posted an "alternate image" version that matches better with the other Ace Attorney characters presented on this blog.]

I started playing Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney before going to law school. I used to always insist that I was "training" for my big days as a lofty attorney. I would never have believed that somebody could make a classic adventure game out of comical parody courtroom drama, but they did. The characters were ridiculous, entertaining, and all around awesome. As I fell knee deep into Dungeons & Dragons character development, I felt like I wanted to find a way to capture some of those characters into the D&D game.

The challenge proved harder than I anticipated. Making Phoenix Wright proved more difficult than I had imagined. What I wanted was some sort of psychic, ranged defender. I wanted to find a character that felt like he did what Phoenix Wright did so the re-skinning would be simple. After months of struggle, I gave up. But, in that time, something else came to mind. There was a character, easily captured within the game rules, that I could make. From that, I began to work.

|

| The fabled "Devil Prosecutor," Miles Edgeworth. |

|

| Former student of Manfred von Karma... |

Warlock aficionados will likely detect that I have broken up the Warlock's Curse power into *four* different abilities on the card. Honestly, that was done to make the Warlock's Curse power more digestible for new players. It is a huge block of text that is quite confusing for players new and old. In this format, I had hoped to present it in a way that was functional and easy to understand. Of course, as I had chosen the Sorcerer-King Pact, I had to introduce a way to track "fell might." It did not take long to develop and system, though, and from that Miles Edgeworth was born into the world of Dungeons & Dragons.

[Note: I posted an "alternate image" version that matches better with the other Ace Attorney characters presented on this blog.]

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

The Gambit of Truth (Part 2)

Once I make a character card for a Dungeons & Dragons character, it isn't especially difficult to continue to level it up over time. That's why I tend to make these as my preferred character sheet. It's easy to read, has everything I generally need, and looks good. Furthermore, I can usually print it on one 8.5x11 sheet of paper (if I shrink the overall aspect a little bit).

One of the Dungeons & Dragons games I play in as a player is with a very peculiar yet surprisingly entertaining group of people. They are great folks but we have the most absurd things happen on a routine basis. When I had to miss a session, I posted my character on my weblog and sent a link to the DM so whoever filled in for me would have an "easy access" character to use. The DM liked the format and started asking me to make character cards for other people that could not make it to a session.

My character is a strange one. In a world dominated by women, where magic is generally forbidden except for those marked by the government, Quintus represents an anomaly. He is a man and a free air mage. He wields the power of lightning and storm independent of the rules of law. As the game progressed, he has been both extremely smooth yet surprisingly naive, even dumb. Complex situations tend to confused him and he tends to rely on the those that he trusts, the other five people he awoke with on that strange day, memories wiped clean.

Having just reached level 5, this represents Quintus shortly after fighting off a terrible beast (a beholder) and watching one of his only friends, the rather impolite and often abrasive witch Asha, die from a blast of an eyestalk. His mastery over the powers of storm have grown but the gnawing hole in his soul, his sense of self, has not changed. Just as he started to decide who he really was, a wander in the company of these strange people he has come to call friend, one of them died horribly.

The strange magician of song, Scarlet, was able to tap some unusual power, ancient forces trapped in the ruins that they found. When Scarlet returned, she had power unimaginable. With it, she was able to not only tear the beholder asunder but also tap the very life essence of the world in an effort to bring Asha back. It is not clear to Quintus what result this will have for him or his "friends."

One of the Dungeons & Dragons games I play in as a player is with a very peculiar yet surprisingly entertaining group of people. They are great folks but we have the most absurd things happen on a routine basis. When I had to miss a session, I posted my character on my weblog and sent a link to the DM so whoever filled in for me would have an "easy access" character to use. The DM liked the format and started asking me to make character cards for other people that could not make it to a session.

My character is a strange one. In a world dominated by women, where magic is generally forbidden except for those marked by the government, Quintus represents an anomaly. He is a man and a free air mage. He wields the power of lightning and storm independent of the rules of law. As the game progressed, he has been both extremely smooth yet surprisingly naive, even dumb. Complex situations tend to confused him and he tends to rely on the those that he trusts, the other five people he awoke with on that strange day, memories wiped clean.

|

| Quintus the Air Mage, level 5! |

|

| A few new things added to the mix... |

The strange magician of song, Scarlet, was able to tap some unusual power, ancient forces trapped in the ruins that they found. When Scarlet returned, she had power unimaginable. With it, she was able to not only tear the beholder asunder but also tap the very life essence of the world in an effort to bring Asha back. It is not clear to Quintus what result this will have for him or his "friends."

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

The Elements of a Classy RPG: Dungeons & Dragons (BECMI)

This post is part of a series concerning Class within the context of Role-Playing Games. For an introduction to the series, see The Elements of a Classy RPG: Introduction.

Dungeons & Dragons has a strange history. Although the game first appeared in 1974, written by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, would eventually be divided in 1977 into two different games: Dungeons & Dragons and Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. The “basic” form of the game would eventually be released from 1977 to 1986 in several boxed sets with multiple revisions, labeled as Basic (Red Box), Expert (Blue Box), Companion (Green Box), Master (Black Box), and Immortal (White) sets. These would eventually be compiled into the Rules Cyclopedia in 1991, corresponding with several mass market items, including the “Big Black Box” and its progeny. The interesting consideration is that for nearly two decades, Dungeons & Dragons had two distinct forms with contradicting rulesets and approaches to play.

My first Dungeons & Dragons set was the BECMI Basic Set, a system of sometimes questionable acceptance in the greater D&D world. I really liked it at the time and I thought it was a great way to learn about the game. The rulebook had a solo adventure to show you how things worked and it provided content to unleash upon your unwitting friends. To this day, I rarely see role-playing game products that introduce players to the game quite like the old Red Box did. There is something about thrusting a potential player right into it through a solo adventure that so many games fail to do. When they created a new mass market product, the “Big Black Box,” they made an even bolder attempt at the solo adventure concept. It used a map, paper stand-up characters, and an involved packet of tabbed pages. However, outside of those products, I did not see that kind of introduction to a role-playing game until the new D&D Essentials Red Box and the Pathfinder Beginner Box. What sets the old Red Box apart for the discussion here was the way that edition of Dungeons & Dragons approached the concept of class.

Out of the box, the base game had seven classes. Character creation was an extremely simple affair. Although the game lists twelve steps, that may be something of an exaggeration. [Note: This twelve step process was taken from the 1991 TSR publication D&D Rules Cyclopedia.] Step 1: Roll for ability scores. Step 2: Choose a character class. Step 3: Adjust ability scores (lowering some to raise your “prime requisite”). Step 4-6: Roll for hit points and money, buy equipment. Step 7-8: Computer other relevant numerical data (saving throws, ability score bonuses, etc). Step 9-11: Choose alignment, name, height, weight, and other “background” elements. Step 12: Earn experience (seriously a step of “character creation”). The whole process probably took less than 15 minutes. The only real choices involved in making your character that had mechanical result were rolling ability scores and choosing a class, with the potential option for tweaking ability scores to better prepare your adventurer. So, class was an extremely big deal in this edition as it said mostly everything about your character.

The four Human classes ran the standard D&D range of “core” classes: Fighter, Thief, Magic-User, and Cleric. If you picked a Fighter, your character was a Human Fighter. There were no Elf or Dwarf fighters in this edition of Dungeons & Dragons. The same was true of the other three core classes. However, the class you chose said a lot about who your character was and how he interacted with the world. Did he wield the powers of magic? Did she invoke the gods? Could he sneak about, undetected by others, and gain access to locked and trapped spaces? Honestly, given the few choices you had in character creation, your class said more about who your character was than any other choice you made. There were no subtle distinctions and no real variants. This Dungeons & Dragons had no Paladins, no Rangers, no Wardens, no Duelists, no Barbarians, and no other sorts of nonsense (at least not as a basic class choice). This was Original Dungeons & Dragons. You picked one of four classes and you filled in the rest on your own.

One peculiarity of this system was the presence of three demihuman classes. To play an Elf or Dwarf in Dungeons & Dragons, you chose that as your class. They occupied a space somewhat different than the Human classes. The Elf was a sort of Wizard/Fighter, allowing strengths of both classes to shine. The Dwarf felt like a Fighter but with unique traits or characteristics unique to a non-human race. The Halfling felt like a very different kind of special fighter, acquiring different abilities that made him more capable in woodland settings. By the Expert Set, they had a different advancement system and very different rules, but in the short term they felt a lot like unique or interesting variants on the standard Human classes. All around, the idea that the fantasy races were described using class felt like a really peculiar choice but it worked in the context of making a game easily approachable by new players. That said, it did result in one peculiar element: all Elf, Dwarf, or Halfling adventurers were very similar to one another, potentially even exactly the same. An astute player may wonder: what about Dwarven Priests or Elven Thieves? As far as player characters were concerned, there was no such thing.

This way Dungeons & Dragons handled class is interesting when compared to other games. Your class says everything about you character mechanically. It says a lot about his place within the world yet it leaves a great deal of room for you to fill in the blanks. Was your Fighter a brave, stalwart knight, clad in the shiniest armor in the realm? Perhaps your Fighter was a dueling swashbuckler, fighting off enemies with a deft blade and clever wit. Maybe that Fighter was a wild tribesman from the Far North, clad in hide and swinging a mighty axe at his foes. They were all Fighters and, to that extent, all the same. Yet, by not saying much about the character, it did allow you, as the player, an opportunity to fill it in as you thought relevant. It just so happened that any choices you made about your character would not mechanically impact your character unless your Dungeon Master wanted them to (and made up some rule to provide for it).

At later levels, the core classes began to see some variety in the options available. Fighters could choose to become Paladins, Avengers, or Knights. Clerics could choose to become a Druid. Wizards and Thieves would have to choose whether to become free agents or lords. Although available, these options to further customize your class were few and far between. In fact, most characters would have roughly one or two choices to make throughout the adventuring career. They usually amounted to choosing between a traveling lifestyle or that of a landed ruler. Would you have a stronghold or would you become an agent of an existing lord, guild, or priesthood? With all that being said, the mechanical elements were light compared to later editions of the game. It made character advancement simple but not terribly enthralling.

It seems very strange to look back on so definitive a game and realize that it did not provide a great deal of options for players with respect to character advancement. A player could make two Fighters, creating one as a fur-clad barbarian with axe and the other a dashing swashbuckler with rapier, and both would function identically outside of their randomly rolled ability scores and weapon choice. Maybe this dearth of features or options are why an Advanced version of Dungeons & Dragons felt so necessary for some players. Perhaps this fundamental lack of options, features, or interesting things to meddle with is why so many people who played the game began making up their own rules. Class provided you only the most limited framework with which to build a character. It was up to you, be it player or Dungeon Master, to fill in the interesting details. Maybe wearing lighter armor gave your swashbuckler a bonus in a way that an armor-clad knight would not have. Maybe your group felt the need to create your own classes to fill the holes. Nonetheless, I cannot help but feel like it would have been nice if the game gave players something to make each character feel unique from another character of the same class.

It is a strange thing to look back at a game system I loved so much as a youth and find that it no longer feels welcome amongst my stable of interesting role-playing games. It had its interesting points, to be sure, but that old systems sits in a weird place in the modern game world: it is too complicated and fussy to fit in with modern story games but wholly unsophisticated (complicated?) enough when compared to modern tabletop RPGs. The game’s use of a class system is so encompassing yet so fundamentally uninteresting as to give a player like me pause. Unlike a game like Rifts, this original Dungeons & Dragons does not supplement its simple class options with a vast range of selectable classes nor does it allow the mixing of different classes in unique ways like Final Fantasy. The class system presented here, outside of its bare simplicity, does not bring much to the table when it comes to looking at class within a RPG. As it stands, this Dungeons & Dragons serves best as a gateway game, introducing players to the concept and then quickly turning them to more sophisticated options.

|

| Dungeons & Dragons: Basic Set (1977-1983) |

Dungeons & Dragons has a strange history. Although the game first appeared in 1974, written by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, would eventually be divided in 1977 into two different games: Dungeons & Dragons and Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. The “basic” form of the game would eventually be released from 1977 to 1986 in several boxed sets with multiple revisions, labeled as Basic (Red Box), Expert (Blue Box), Companion (Green Box), Master (Black Box), and Immortal (White) sets. These would eventually be compiled into the Rules Cyclopedia in 1991, corresponding with several mass market items, including the “Big Black Box” and its progeny. The interesting consideration is that for nearly two decades, Dungeons & Dragons had two distinct forms with contradicting rulesets and approaches to play.

My first Dungeons & Dragons set was the BECMI Basic Set, a system of sometimes questionable acceptance in the greater D&D world. I really liked it at the time and I thought it was a great way to learn about the game. The rulebook had a solo adventure to show you how things worked and it provided content to unleash upon your unwitting friends. To this day, I rarely see role-playing game products that introduce players to the game quite like the old Red Box did. There is something about thrusting a potential player right into it through a solo adventure that so many games fail to do. When they created a new mass market product, the “Big Black Box,” they made an even bolder attempt at the solo adventure concept. It used a map, paper stand-up characters, and an involved packet of tabbed pages. However, outside of those products, I did not see that kind of introduction to a role-playing game until the new D&D Essentials Red Box and the Pathfinder Beginner Box. What sets the old Red Box apart for the discussion here was the way that edition of Dungeons & Dragons approached the concept of class.

|

| The "Big Black Box" of the early 1990s. |

|

| This guy is a Fighter. |

|

| What do you mean Halfling is a "class" in this edition? |

|

| Hey! These guys are Fighters, too. |

|

| The Druid, relegated to level 9 Cleric upgrade. |

At later levels, the core classes began to see some variety in the options available. Fighters could choose to become Paladins, Avengers, or Knights. Clerics could choose to become a Druid. Wizards and Thieves would have to choose whether to become free agents or lords. Although available, these options to further customize your class were few and far between. In fact, most characters would have roughly one or two choices to make throughout the adventuring career. They usually amounted to choosing between a traveling lifestyle or that of a landed ruler. Would you have a stronghold or would you become an agent of an existing lord, guild, or priesthood? With all that being said, the mechanical elements were light compared to later editions of the game. It made character advancement simple but not terribly enthralling.

It seems very strange to look back on so definitive a game and realize that it did not provide a great deal of options for players with respect to character advancement. A player could make two Fighters, creating one as a fur-clad barbarian with axe and the other a dashing swashbuckler with rapier, and both would function identically outside of their randomly rolled ability scores and weapon choice. Maybe this dearth of features or options are why an Advanced version of Dungeons & Dragons felt so necessary for some players. Perhaps this fundamental lack of options, features, or interesting things to meddle with is why so many people who played the game began making up their own rules. Class provided you only the most limited framework with which to build a character. It was up to you, be it player or Dungeon Master, to fill in the interesting details. Maybe wearing lighter armor gave your swashbuckler a bonus in a way that an armor-clad knight would not have. Maybe your group felt the need to create your own classes to fill the holes. Nonetheless, I cannot help but feel like it would have been nice if the game gave players something to make each character feel unique from another character of the same class.

|

| Madness? No, this is Dungeons & Dragons!!! |

Monday, June 25, 2012

D&D: The Clone Wars (Part 7)

The Seeker ended up being a bit more difficult than I would have originally imagined. Despite having throwing weapon powers, the "out of the box" Seeker only has two throwing weapon proficiencies: javelin and dagger. [Technical Note: The Seeker also has proficiency with a few odd throwing weapons added in later supplements, including the widow's knife and short spear, but I did not count those.] Neither was especially enthralling of a choice. I wanted something that could be used one handed but that could be used in a pair, like Rex's Hand Blasters. I originally considered the Hand Axe or Throwing Hammer, both reasonable choices, but I found taking two weapons did not actually gain anything. I flirted with a few exotic Dark Sun weapons, but eventually something came to mind: the Net.

|

| Anakin's dependable clone commander, Captain Rex. |

|

| Rex is heavy on close-range monster control. |

In my research of using Nets, another feat path came up: the Foamgather Heritage feats. Foamgather Warrior, gave a +1 (untyped) bonus to attacks made with a net. In addition, it granted use of a special Melee or Ranged net attack which could grab (immobilize) and reposition enemies. This seemed like a really good choice for Captain Rex, as well. Not able to decide between the two, I decide to go with both sets of feats (Net Training and the Foamgather feats).Way back in the early days of Fourth Edition (October 2008!), Dragon magazine featured an article on gladiators and gladiatorial combat. In it, they introduced rules for "iconic" gladiatorial weapons, including Nets, Whips, and Bolas. As these weapons were all somewhat exotic and generally only powerful within the context of special abilities, they included multi-class paths for gaining proficiency, special abilities, and new powers with specific weapons. The basic net feat, Net Training, grants proficiency with the Net and the special ability to slow targets with each blow. That seemed an interesting choice, so I went with it.

As it ends up, this is a character for which a few more levels would yield interesting results. The two additional feats that would help improve Rex's performance are Flail Expertise, which would give an additional +1 to hit with the next and allow him to prone targets instead of slide them, and Far Throw, which would increase his Ranged capabilities from 2/5 to 4/7. Honestly, the only concern at that point would be his armor, as he would rely on being "in the mix" to get his controlling done but be susceptible to attack. Perhaps all he needs is a good defender, like Jedi Knight Anakin Skywalker...

Saturday, June 23, 2012

Dungeon Gear Solid: Dragon Eater

The Fourth Edition of Dungeons & Dragons game had flirted with the idea of an Assassin a few years into the run. When the Essentials line was released, they began play-testing an "Essentials" Assassin, a variant meant to capture more of the iconic, old-school Assassin. When first released, I could not help but think that somebody had really just been praying for a re-imagining of the old First Edition Assassin. It seemed interesting, but I was not sure how I felt about it in play. My biggest concern was how the Poison system would play out. Eventually, the "final" version was released as part of Heroes of Shadow and I began to think about how the class would fit into the overall context of the game. It seemed weird, but it started to seem like something different and interesting. The Assassin used strange weapons and had interesting hand-to-hand abilities that warranted further investigation.

When I began making Dungeons & Dragons character cards for my local D&D Encounters game, I started by trying to find classes that would easily fit into specific, iconic characters. The Red Scales Assassin felt like somebody who I had already seen, an iconic character that needed realization within the Dungeons & Dragons context. I realized that knocking enemies prone, stabbing them with a knife, and choking them from behind fit right into a favorite character of mine... Naked Snake from Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater. With that in mind, I sat down to the character builder and began working.

|

| CODEC: 140.85 |

|

| You haven't been practicing your CQC, Snake... |

It took me some time figuring out quite how Snake would work within the context of Dungeons & Dragons. The Red Scale Assassin seemed to be near perfect. Garrote attack for a CQC choke. At-will attack that left the enemy prone to represent a CQC body toss. Special knife attacks for using poison. It was just a matter of making it all mesh together properly and naming things such that they felt very ... Snake-like. Honestly, the only thing this character was missing was an absurd array of camouflage to shift between. To be honest, I had half considered making him a Changeling just so I could have an ability that fit with the shifting of camo.

I should make one note about this character for the Fourth Edition rules aficionados out there. I have essentially done away with the garrote, despite it being essential to one of his attacks. The Executioner Assassin has an ability (Quick Swap) that allows him to sheath one weapon and draw another as a Free Action. In addition, Snake has the Master at Arms feat which allows him to sheath one weapon and draw another as a Minor Action. Keeping both of those in mind, I have essentially done away with switching to the garrote as part of Snake's move set. If he wants to choke somebody out (CQC Choke), he does (assuming he meats the hidden requirement). In the context of the character, it works just fine. In the mechanical context, a picky DM can just accept the fact that he is constantly switching his weapons around such that he uses the appropriate weapon for the attack he intends to perform.

I should make one note about this character for the Fourth Edition rules aficionados out there. I have essentially done away with the garrote, despite it being essential to one of his attacks. The Executioner Assassin has an ability (Quick Swap) that allows him to sheath one weapon and draw another as a Free Action. In addition, Snake has the Master at Arms feat which allows him to sheath one weapon and draw another as a Minor Action. Keeping both of those in mind, I have essentially done away with switching to the garrote as part of Snake's move set. If he wants to choke somebody out (CQC Choke), he does (assuming he meats the hidden requirement). In the context of the character, it works just fine. In the mechanical context, a picky DM can just accept the fact that he is constantly switching his weapons around such that he uses the appropriate weapon for the attack he intends to perform.

Friday, June 22, 2012

Four Letters Only, Please (PWA 2.1)

Phantasy Warrior Advance: Four Letters Only, Please

I always wondered, while playing the host of old console games, why I only had a small number of letters with which to name my character. Four letters? What kind of name do you get out of four characters? Of course, in English, four letters allows you a whole host of terrible names. Although I never did it myself, I had friends who used to run the gauntlet of "four letter words" for character names.

During the 16-bit era, games started adding two extra letters to character names. Of course, I never really noticed it at the time. I just suddenly had the opportunity to name characters things that were longer than "Alex" or "Rolf." After a while, you get surprisingly tired of every character having four letter names. Of course, even with two extra letters, occasionally you get characters who have suspicious names, such as Final Fantasy VI's "Cyan." I remember having debates as to how his name was supposed to be pronounced. If only we knew the intended name was "Cayenne."

I did not really notice nor comprehend the whole name issue until Final Fantasy VII came out for the Sony Playstation. They had made a big fuss about expanding the character count for names all the way up to nine. Nine! All so they could fit the name "Sephiroth" into the character name boxes. Nowadays, it seems that I rarely encounter games where standard names do not fit. Extremely long names may be an issue, but the run-of-the-mill names like Andrew or Daniel fit in just fine.

I always wondered, while playing the host of old console games, why I only had a small number of letters with which to name my character. Four letters? What kind of name do you get out of four characters? Of course, in English, four letters allows you a whole host of terrible names. Although I never did it myself, I had friends who used to run the gauntlet of "four letter words" for character names.

During the 16-bit era, games started adding two extra letters to character names. Of course, I never really noticed it at the time. I just suddenly had the opportunity to name characters things that were longer than "Alex" or "Rolf." After a while, you get surprisingly tired of every character having four letter names. Of course, even with two extra letters, occasionally you get characters who have suspicious names, such as Final Fantasy VI's "Cyan." I remember having debates as to how his name was supposed to be pronounced. If only we knew the intended name was "Cayenne."

I did not really notice nor comprehend the whole name issue until Final Fantasy VII came out for the Sony Playstation. They had made a big fuss about expanding the character count for names all the way up to nine. Nine! All so they could fit the name "Sephiroth" into the character name boxes. Nowadays, it seems that I rarely encounter games where standard names do not fit. Extremely long names may be an issue, but the run-of-the-mill names like Andrew or Daniel fit in just fine.

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

The Elements of a Classy RPG: Final Fantasy

This post is part of a series concerning Class within the context of Role-Playing Games. For an introduction to the series, see The Elements of a Classy RPG: Introduction.

After reviewing the system used in Rifts, it seemed appropriate to consider a system that feels completely different than the epic Palladium system. I looked around, hoping to find a system that de-emphasized the character elements (story, background, history, etc) part of a character's class. Final Fantasy is not a tabletop RPG, but it still has a lot to say about the concept of class (or “job”) within the realm of role-playing games. Although different games within the series used somewhat different game mechanics for character improvement, especially regarding how new abilities or skills are acquired, the “job system” has been popular enough in the series to reappear several times in several slightly varied forms. First introduced in Final Fantasy III, the system reappeared in Final Fantasy V, Final Fantasy Tactics (et seq.), and Final Fantasy X-2. When considering the different class systems in various role-playing games, this "job system" within the Final Fantasy series presents a sort of extreme for what class means within a role-playing game. The way that the game handles class is different and interesting enough that it warrants consideration in the grand analysis of class-based systems. This is especially relevant when you consider that most people are first exposed to a class-based RPG system from games like Final Fantasy, so it informs what expectations people bring to the table.

The “job system” is interesting because it feels a lot like a class system mechanically but does not necessarily feel like one thematically. When I say it has no effect thematically, I mean to say that it has no effect on the character's story. Just because your character is now a Dragoon or a Dancer is irrelevant to the character outside of powers and abilities. The character’s history, background, story, personality, training, and place within the story are completely independent of what job they may have selected. Faris, the pirate captain in Final Fantasy V, can be a Red Mage, a Thief, a Geomancer, or any job you want. The job system is flexible enough that you can even change a character’s job whenever not in combat. Yet, despite whatever class you may choose for her, Faris is still the pirate captain and lost heir of the Kingdom of Tycoon. Whether she be a Black Mage or a Mime, her place within the greater story remains exactly the same. In fact, there are no circumstances whatsoever where a character’s job (or job experience) will impact the story elements.

This idea seems somewhat contrary to how class is normally presented. In a game like Final Fantasy V, a character’s class (or job) is nothing more than an expression of what that character does in battle. It provides abilities, powers, features, and other ways to interact in battle. The player selects a specific class for each character and that determines what that character can do. As they fight battles, characters gain “job points” along with their experience points. While experience points influence the character’s level, affecting their game statistics, these job points are used to advance the progress within that specific job. Eventually, more job-based abilities become available. Some abilities are passive while others are new active abilities available for use in battle. This kind of advancement, gaining new abilities and powers, is comparable to the kind of advancement one sees in other role-playing games. However, a major difference here is that a character can change their class at any time outside of combat with no penalty. Further, the system allows some unique blending of the jobs. These features are what make the Final Fantasy V system so interesting mechanically.

Every character has four basic combat ability slots: Fight (for attacking foes), a job based ability (based on which job is currently selected), an optional slot (for equipping additional abilities), and Item (for using items). The interesting feature in that set of abilities is the optional slot. The optional slot serves two purposes. The more obvious purpose of the slot is to allow a character to equip an optional ability gained by advancing within the class. For example, the Monk class learns both “Focus” and “Chakra,” abilities that can be equipped to the optional slot. Some passive abilities can also be equipped in that optional slot, such as “HP +20%,” which boosts a character’s overall hit points. But, the more interesting feature of the optional slot is the ability to equip abilities learned from other jobs. Want to use Chakra as a Knight? Get to job level 3 as a Monk, change to the Knight class, and equip it in the optional slot. Want to fight bare-fisted as a White Mage? Get to job level 2 as a Monk, change to White Mage, and equip Barehanded. With this, you can have Black Mages wielding two-handed swords, Blue Mages casting White Magic, or any sort of ridiculous combination. This becomes even more interesting when a character selects the “Freelancer” job, which has the innate abilities of every “mastered” job and to equip two different job abilities. Thus, by mastering a job, that character’s “default” job becomes more powerful.

|

| So many jobs, so many different abilities! |

The “job system” is interesting because it feels a lot like a class system mechanically but does not necessarily feel like one thematically. When I say it has no effect thematically, I mean to say that it has no effect on the character's story. Just because your character is now a Dragoon or a Dancer is irrelevant to the character outside of powers and abilities. The character’s history, background, story, personality, training, and place within the story are completely independent of what job they may have selected. Faris, the pirate captain in Final Fantasy V, can be a Red Mage, a Thief, a Geomancer, or any job you want. The job system is flexible enough that you can even change a character’s job whenever not in combat. Yet, despite whatever class you may choose for her, Faris is still the pirate captain and lost heir of the Kingdom of Tycoon. Whether she be a Black Mage or a Mime, her place within the greater story remains exactly the same. In fact, there are no circumstances whatsoever where a character’s job (or job experience) will impact the story elements.

|

| So much to master, so little time! |

|

| Assign abilities as you will, no matter how absurd. |

What is important to understand about the Final Fantasy V job system, as I stated before, was that all of this was independent of the character’s role in the story. The same is true of the system that appeared in Final Fantasy Tactics. Galuf, Lenna, Ramza, or T.G. Cid have no different interactions with the characters, locations, or events within the story based on their currently selected job or any previously trained jobs. It just does not matter at all. This seems peculiar when you consider how much weight people give to class as a definition of character in tabletop role-playing games. Yet, the idea of having character class provide abilities, traits, or powers is not unusual in tabletop games. Examining this kind of job system provides a perspective worth considering when thinking about what the concept of class means within role-playing games.

Monday, June 18, 2012

Dungeons & Dragons: Yuri's Revenge

When I first started making character cards for Dungeons & Dragons Encounters, I tried to explore character classes that were not well represented within the already existing set of characters. Specifically, I wanted to make characters that people did not normally play. The existing cards covered a broad range, but mostly focused on Essentials content. What I wanted was something ... different.

Psionic characters did not get a lot of love from the D&D community when they first arrived, at least amongst my friends. As a friend put it, Players Handbook 3 was "holding the Monk hostage." Eventually, the fact that these classes were different became an interesting thing to explore. Eventually, these kinds of differences would be made a major design choice as Essentials classes shattered the old mold of At-Will/Encounter/Daily.

As it ends up, I found psionic classes somewhat different to develop for. They are a bit strange. I figured the easiest way to make a cool character card for a psionic character was to find some iconic character that was psychic. After a little thought, I realized that one of my favorite Udo Kier characters would fit the bill nicely.

I will admit that I thought Udo Kier did an incredible job playing Yuri in Command & Conquer: Red Alert 2. Command & Conquer had been a series that made a name for filming live actors for story sequences, but those "actors" often tended to be design staff. They kicked it up a notch when they hired James Earl Jones for Tiberian Sun, but they made the mistake of taking themselves too seriously. Red Alert 2 was done by a team that apparently had very little interest in taking themselves too seriously. The game's introduction even lets you know it intends to be absurd as it features mind-controlled squid, a mind controlling telephone handset, and giant Soviet zeppelins flying over New York. Somehow, the over-the-top villain Yuri, special psychic advisor to Soviet Premier Romanov, seemed a perfect match for the kinds of ridiculous pre-made characters I have become fond of building.

I originally developed Yuri as one of my early pre-made character cards. When I went looking for a character race that utilized Intelligence and Charisma, I somehow ended up choosing a Tiefling. As I recall, I first constructed the character shortly after Heroes of the Forgotten Kingdoms had been released. Thus, the original Yuri had some peculiar artifacts from the racial choice (fire resistance, fire reaction attack). I never liked that and had even re-written his resistance as cold resistance, calling it "Soviet Hardening" or "Soviet Cold Training." Luckily, Essentials started a way of "upgrading" for all of the races featured in print, which provided a new, better option for our Soviet Supermind: the Kalashtar.

When I went to "touch him up" to throw up on the weblog, I realized that all off the old standard races had been upgraded to feature a choice for attribute bonuses. Suddenly, the Kalashtar was a good choice as it fit the attributes I was looking for while also granting telepathy and other psychic related abilities. Thus, the new version of Yuri was born.

The big "trick" with this character card was setting up the Augment powers and the power points. Power points would prove to be exceptionally easy as I had already done abilities with multiple use blocks. The augment powers did not end up being especially difficult as I had done something similar of the Monk's Full-Discipline powers.

Psionic characters did not get a lot of love from the D&D community when they first arrived, at least amongst my friends. As a friend put it, Players Handbook 3 was "holding the Monk hostage." Eventually, the fact that these classes were different became an interesting thing to explore. Eventually, these kinds of differences would be made a major design choice as Essentials classes shattered the old mold of At-Will/Encounter/Daily.

As it ends up, I found psionic classes somewhat different to develop for. They are a bit strange. I figured the easiest way to make a cool character card for a psionic character was to find some iconic character that was psychic. After a little thought, I realized that one of my favorite Udo Kier characters would fit the bill nicely.

|

| "Only complete faith in Yuri can protect you." |

|

| "Be one with Yuri." |

|

| Yuri and Stalin. |

When I went to "touch him up" to throw up on the weblog, I realized that all off the old standard races had been upgraded to feature a choice for attribute bonuses. Suddenly, the Kalashtar was a good choice as it fit the attributes I was looking for while also granting telepathy and other psychic related abilities. Thus, the new version of Yuri was born.

The big "trick" with this character card was setting up the Augment powers and the power points. Power points would prove to be exceptionally easy as I had already done abilities with multiple use blocks. The augment powers did not end up being especially difficult as I had done something similar of the Monk's Full-Discipline powers.

Sunday, June 17, 2012

Phantasy Warrior Advance

Many years ago, a very good friend that I was living with starting putting together his own webcomic. I was quite impressed with the idea and wanted a piece of the action. As I had no artistic skill, no partner to work with, and very little in the way of hope, I cobbled together a very crude comic based on sprites that I had found from old Final Fantasy games.

When I began, I had a definitive idea as to what I hoped to accomplish. I imagined a classic looking console role-playing game that seemed to be suspiciously affected by a lack of budget. Of course, that idea did not necessarily translate all that well and most of it just ended up being a series of jokes about whatever games I had played throughout my life. I did fifty "issues" of the comic before concluding it. It was absurd. It was ridiculous. But, it was fun to do and I learned a lot.

A few years later, I started a similar process, trying to tie a much bigger story to the whole thing while trying to find a way to integrate the original comic into something new. I was not sure what it was I had hoped to accomplish but I worked at it. I experimented with new artistic methods, new images, and new potential ideas. I even began using peculiar art techniques as applied to output photos from The Sims 2. In the end, I never got especially far with it that time, but I did end up with a growing database of sprites that I had either extracted from various sources or began crafting on my own.

I actually took another "stab" at the process some time afterward, attempting to integrate all of the different ideas into one coherent story (again). Of course, that effort seemed to last less time than the previous, but I did manage to take some measurable amount of content out of the process. The story was set in an actual console game and the main character would be a sort of "Captain N" style transport from the real world into the game work. Most importantly, I finally created an iconic cover for the fantasy game in question: Phantasy Warrior.

When I started, I wanted the box to look like something that you would expect to see in the early days of the Nintendo Entertainment System (Famicom). I spent a lot of time looking at old Nintendo game box art, trying to capture the iconography and style of that art. Honestly, it was surprising to discover how bad most of it was. However, it gave me a solid idea as to how my potential box art should look.

The end result was actually arranged in Comic Life by plasQ (which, comically, I cannot recover). Although all of the individual images were done in either Adobe Photoshop or occasionally Adobe Illustrator, I found it "easier" to do comic-style layouts in Comic Life at the time. I did not have sufficient experience working in Illustrator or Photoshop to accomplish my layout goals, so I relied heavily on the software package provided by PlasQ.

I also created a back cover, using the same kinds of old Nintendo game boxes as models. I hoped to capture the flavor of some of those old game boxes, including the astounding hyperbole ("a fantasy world beyond imagination!"), really uninformative screen shots (even framed to look like a classic CRT perspective), and a game description that says very little about what will actually go on when you put the game in your system.

One of the elements I spent a great deal of time on was the "Adventure Series" marker that appears on both the front and back covers. The first few sets of Nintendo games had quasi-informative symbols on the cover that were meant to inform you of what kind of game you were purchasing. It took me a while to find out what kind of game a RPG would be but I finally found an image of the Metroid box cover, one of the last ones before they eliminated the symbolic system. As it ends up, Metroid was an Adventure Series game, as contrasted to an Action Series or a Sports Series. I felt this was the closest and best I would get so I did my best to recreate the symbol for inclusion on my box cover.

The reason I spend so much time introducing the background behind the Phantasy Warrior comics I throw into the blog is that the comic as it appears now is actually heavily influenced by the work I did before. In fact, although the comic does tend to have a certain amount of geek humor, a lot of the "story" relates back to what I did the first time around. Although I do not intend to fully re-release the original comic, I do expect to reference elements from it (as appropriate). It seemed appropriate to start with the epic packaging I did for the game back in 2008-09.

When I began, I had a definitive idea as to what I hoped to accomplish. I imagined a classic looking console role-playing game that seemed to be suspiciously affected by a lack of budget. Of course, that idea did not necessarily translate all that well and most of it just ended up being a series of jokes about whatever games I had played throughout my life. I did fifty "issues" of the comic before concluding it. It was absurd. It was ridiculous. But, it was fun to do and I learned a lot.

A few years later, I started a similar process, trying to tie a much bigger story to the whole thing while trying to find a way to integrate the original comic into something new. I was not sure what it was I had hoped to accomplish but I worked at it. I experimented with new artistic methods, new images, and new potential ideas. I even began using peculiar art techniques as applied to output photos from The Sims 2. In the end, I never got especially far with it that time, but I did end up with a growing database of sprites that I had either extracted from various sources or began crafting on my own.

|

| It does have a certain Pokemon look to it. |

When I started, I wanted the box to look like something that you would expect to see in the early days of the Nintendo Entertainment System (Famicom). I spent a lot of time looking at old Nintendo game box art, trying to capture the iconography and style of that art. Honestly, it was surprising to discover how bad most of it was. However, it gave me a solid idea as to how my potential box art should look.

The end result was actually arranged in Comic Life by plasQ (which, comically, I cannot recover). Although all of the individual images were done in either Adobe Photoshop or occasionally Adobe Illustrator, I found it "easier" to do comic-style layouts in Comic Life at the time. I did not have sufficient experience working in Illustrator or Photoshop to accomplish my layout goals, so I relied heavily on the software package provided by PlasQ.

|

| Writing bad copy is tough, as it ends up. |

One of the elements I spent a great deal of time on was the "Adventure Series" marker that appears on both the front and back covers. The first few sets of Nintendo games had quasi-informative symbols on the cover that were meant to inform you of what kind of game you were purchasing. It took me a while to find out what kind of game a RPG would be but I finally found an image of the Metroid box cover, one of the last ones before they eliminated the symbolic system. As it ends up, Metroid was an Adventure Series game, as contrasted to an Action Series or a Sports Series. I felt this was the closest and best I would get so I did my best to recreate the symbol for inclusion on my box cover.

The reason I spend so much time introducing the background behind the Phantasy Warrior comics I throw into the blog is that the comic as it appears now is actually heavily influenced by the work I did before. In fact, although the comic does tend to have a certain amount of geek humor, a lot of the "story" relates back to what I did the first time around. Although I do not intend to fully re-release the original comic, I do expect to reference elements from it (as appropriate). It seemed appropriate to start with the epic packaging I did for the game back in 2008-09.

Friday, June 15, 2012

Because a Real Hero Applied Two Months Ago (PWA 1.2)

Phantasy Warrior Advance: Because a Real Hero Applied Two Months Ago

I actually applied for the LSAT pretty late in the process. I never intended to go to law school until I found out that I had essentially zero chance to get into the Ph.D. program I had applied for. As much as my old boss hated to hear it, law school was not my first choice on leaving the Navy.

That being said, I was surprised at all of the timing issues involved in applying for law school. Certain tests had to be done by certain days. Some test dates were too late. Certain schools had application deadlines by certain dates, but many had "rolling" admissions. Some had priority admissions by certain dates with other applications acceptable until ... whenever? Of course, I managed to wade through most of the paperwork and bureaucracy, but at times it was frustrating since my whole law school adventure was very last minute.

I sometimes wonder what it would be like if games started being as draconian as the real world. "I'm sorry, but you forgot to level up your character by the requisite deadline, so you will be unable to level up your character until the next leveling window." Maybe there is something to be said about applying "real world stress" within the context of the game, but that just seems like negative fun.

I actually applied for the LSAT pretty late in the process. I never intended to go to law school until I found out that I had essentially zero chance to get into the Ph.D. program I had applied for. As much as my old boss hated to hear it, law school was not my first choice on leaving the Navy.

That being said, I was surprised at all of the timing issues involved in applying for law school. Certain tests had to be done by certain days. Some test dates were too late. Certain schools had application deadlines by certain dates, but many had "rolling" admissions. Some had priority admissions by certain dates with other applications acceptable until ... whenever? Of course, I managed to wade through most of the paperwork and bureaucracy, but at times it was frustrating since my whole law school adventure was very last minute.

I sometimes wonder what it would be like if games started being as draconian as the real world. "I'm sorry, but you forgot to level up your character by the requisite deadline, so you will be unable to level up your character until the next leveling window." Maybe there is something to be said about applying "real world stress" within the context of the game, but that just seems like negative fun.

Thursday, June 14, 2012

D&D: The Clone Wars (Part 1, revisited)

After working through a large number of Dungeons & Dragons characters, I started to rethink a few of my original creations. Specifically, some of them seemed like they could be done differently or, in a few cases, done a little bit better. Rather than just go back and replace the old character cards, I thought it would be perfectly acceptable to make a new card representing a different "version" of the iconic character.

The first character I chose for this was Anakin Skywalker. The reason was not that I had a problem with the original Anakin card I made but that I found a different (arguably, better) character match for Anakin. I had read a bit on the Berserker class, first presented in Heroes of the Feywild, and I thought it seemed especially appropriate for Anakin. A defender who can loose her cool and go wild as a striker seemed like an interesting fit for the young Jedi Knight.

What was most interesting about this was the number of abilities that suspiciously overlapped. The original character was a Fighter with a Power Strike. Now, as a Half-Orc, he has almost the same ability. Thus, to a certain extent, I was able to ground him to the original Anakin Skywalker character I made.To a certain extent, I feel like this Anakin is more like what I expect Anakin to feel like. In the beginning of battle, he is calm and collected. He aids his comrades and defends them from attack. But, once bloodied, the calm and cool Anakin Skywalker goes into his own style of rage, striking his foes with the power of his anger and fury. Thus, he succumbs just a bit to that Dark Side gnawing away at his soul.

The Berserker is an interesting class. Starting out as a stalwart defender and then losing it to strike down your foes is an interesting way to work the mechanic. Unfortunately, it is quite easy to forget things like the AC bonus from the Defender's Aura, which can make him less effective as a defender. Hopefully, anybody that chooses to use Anakin will not suffer that problem.

The first character I chose for this was Anakin Skywalker. The reason was not that I had a problem with the original Anakin card I made but that I found a different (arguably, better) character match for Anakin. I had read a bit on the Berserker class, first presented in Heroes of the Feywild, and I thought it seemed especially appropriate for Anakin. A defender who can loose her cool and go wild as a striker seemed like an interesting fit for the young Jedi Knight.

|

| A slightly different Anakin Skywalker.. |

|

Capturing the Fury in an easy-to-read fashion was tough.

|

The Berserker is an interesting class. Starting out as a stalwart defender and then losing it to strike down your foes is an interesting way to work the mechanic. Unfortunately, it is quite easy to forget things like the AC bonus from the Defender's Aura, which can make him less effective as a defender. Hopefully, anybody that chooses to use Anakin will not suffer that problem.

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

The Elements of a Classy RPG: Rifts

This post is part of a series concerning Class within the context of Role-Playing Games. For an introduction to the series, see The Elements of a Classy RPG: Introduction.

Although it is not any sort of proper order at all, I want to start with the class system used in the Palladium system. Palladium Books published a number of different role-playing games, including Heroes Unlimited, Rifts, Ninjas & Superspies, Beyond the Supernatural, After the Bomb, and Palladium Fantasy. They also had licensed titles such as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Robotech. All of them used the same (or similar) game mechanics. Most of the games used a class system, referring to a character’s class as O.C.C., or Occupational Character Class. In addition, some games utilized classes based on race instead of occupation, known as R.C.C., or Racial Character Class. [A few games also utilized P.C.C., or Psychic Character Class, but that designation did not survive to Rifts.] Eventually, all of this would come together within the Rifts setting, bringing the Palladium Megaverse together in a grim future. Thus, I want to look at the system as it appeared in Rifts (and its many supplements) in order to get a sense of what the O.C.C. system entailed.

The Rifts core rulebook had a wide variety of classes for players to choose from: Rogue Scholar. Wilderness Scout. Cyber Knight. Crazy. You chose your class at character creation and that defined the character in mechanics, concept, and story. It defined what kind of skills your character had, what kind of special features she might have, what kind of money and equipment she would start with, and how she advanced through play. It also said a lot about where your character came from, how she got her start, and something about her place in the universe. In a way, the Palladium O.C.C. or R.C.C. defined almost everything about your character (outside of race). There were not a lot of details to change within any O.C.C. and once you chose it, your character was generally stuck with it. Occasionally, a character class would allow for a type of major change or “out” from the confines of the class, but such a thing was mechanically rare (i.e., the Juicer O.C.C., a warrior hooked up to a sophisticated drug injection system, could try to break her addiction to the drug treatment, which would result in a longer life span but substantially fewer abilities, leading to a less functional character class). However, with few exceptions, this type of transition was never explicitly presented within the ruleset. A player who wanted his or her character to undergo a fundamental life change would likely have to discuss it with the Game Master.

The interesting thing about the Palladium system was that there were a huge number of O.C.C. and R.C.C. choices available. I even remember seeing Rifts sourcebooks advertising the number and variety of new O.C.C. selections available. Consider a look at this purported class master list. On it, you can find Bandit Highwayman, Bandit (Peasant Thug), Reaver Bandit/Raider, Bandit/Pecos Raider, and Vanguard Brawler Thug (a R.C.C.). Although covering all sorts of Bandits and Thugs, I failed to mention thieves, represented by Gypsy Thief, Gypsy Wizard Thief, and Professional Thief. In the Palladium universe, there was something different enough about these different types of characters to warrant different classes individual advancement tables and rules. Sometimes, you would even find an O.C.C. that felt like it was there simply as a joke. The Vagabond O.C.C., from the Rifts core rulebook, fits an important niche within the greater Rifts universe (that is, everybody who is not something fancy and special) but feels mechanically like half of a class, with less skills, equipment, and abilities than any other class in the book.

Just by looking over the class system of the Palladium role-playing system, it seems obvious that class is less about mechanical features and more about filling a specified character concept within the greater universe. It was less the game mechanics that mattered but the place within the overall world that mattered. In Rifts, it was not enough to have a soldier of the sinister Coalition as a class in the game; the game had some six or seven in the base rulebook alone. How a Borg differed from a Coalition Borg, or a Psi-Stalker differed from a Coalition Psi-Stalker, was obviously sufficient to warrant individual classes: one was a member of the Coalition military while the other was not. Granted, there may be particular mechanical differences between the classes, but the fundamental difference rested in its origin.

The distinctions between classes sometimes feel almost cheap. A Glitter Boy O.C.C. has but one identifying feature: it starts with a giant “pre-war” suit of power armor (called a Glitter Boy). The power armor is its primary class feature. A Coalition Grunt is not especially different than any other type of bounty hunter, grunt, or mercenary, but the Coalition Grunt is a unique O.C.C. because it represents a character who is (or once was) a member of the Coalition and retains his or her specialized body armor. Since the classes were so specific in theme and representation, hundreds were available to fill each unique background, story, or character concept.

Considering all of this, Palladium represents a sort of extreme within the RPG system. Hundreds of classes, each representing a specified niche within the universe. To make a Coalition Grunt and then insist he was something other than a grunt of the all-mighty Coalition seemed to be missing the point. You picked Coalition Grunt because your character was a basic soldier within the Coalition military (or, was recently such a soldier). Although Rifts, like any RPG, promoted the use of your imagination, your character would generally fit within one of the pre-made character molds presented by the creators. This somewhat unique class system presented a peculiar economic possibility because it allowed the creators to continue to publish new sourcebooks with new classes. However, as the number of classes continued to soar, the distinctions between classes seemed to decline. The proliferation of classes ended with very few being especially unique or interesting outside of the role it played within the greater Rifts narrative.

All that being said, the Rifts system was interesting in that it gave you, as a player, a character to play. It had a sort of “pick-up-and-play” aspect to it. Pick a Rogue Scientist? Well, you had a pretty good idea that you were a trained scientist, potentially on the run from the Coalition. You likely had discovered or created something that the Coalition wanted or you were attempting to devise some technology that would work against the Coalition’s interests. Rather than ask yourself how your character came to be in the world, Kevin Siembieda provided it in your character’s class description. This is great for a first time player, but I feel that most players want a little bit more in the production of a character than merely slotting into a pre-existing archetype like Rifts provided.

I suspect very few people are interested in playing a game with a class system as presented in Rifts. What it accomplishes in providing a character fixed into the greater story has been easily accomplished by other games, both more simply and more effectively. Instead, the Rifts system ends up becoming nothing more than a horrifying example of bloat within the role-playing world, where the basic ideas of role-playing are pushed aside to get more books on the shelf. Its few strengths are readily outmatched by the absurdity of its weakness, making a framework few should attempt to emulate.

Although it is not any sort of proper order at all, I want to start with the class system used in the Palladium system. Palladium Books published a number of different role-playing games, including Heroes Unlimited, Rifts, Ninjas & Superspies, Beyond the Supernatural, After the Bomb, and Palladium Fantasy. They also had licensed titles such as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Robotech. All of them used the same (or similar) game mechanics. Most of the games used a class system, referring to a character’s class as O.C.C., or Occupational Character Class. In addition, some games utilized classes based on race instead of occupation, known as R.C.C., or Racial Character Class. [A few games also utilized P.C.C., or Psychic Character Class, but that designation did not survive to Rifts.] Eventually, all of this would come together within the Rifts setting, bringing the Palladium Megaverse together in a grim future. Thus, I want to look at the system as it appeared in Rifts (and its many supplements) in order to get a sense of what the O.C.C. system entailed.

|

| The Juicer, the result of Nancy Reagan's failure. |

|

| Perhaps "Adventurer" or "Wanderer" would have sounded more heroic than "Vagabond." |

|

| The Coalition: Better than you simply because of the name. |

|

| No, as it ends up, Glitter Boys do not have special parades every year. |

Considering all of this, Palladium represents a sort of extreme within the RPG system. Hundreds of classes, each representing a specified niche within the universe. To make a Coalition Grunt and then insist he was something other than a grunt of the all-mighty Coalition seemed to be missing the point. You picked Coalition Grunt because your character was a basic soldier within the Coalition military (or, was recently such a soldier). Although Rifts, like any RPG, promoted the use of your imagination, your character would generally fit within one of the pre-made character molds presented by the creators. This somewhat unique class system presented a peculiar economic possibility because it allowed the creators to continue to publish new sourcebooks with new classes. However, as the number of classes continued to soar, the distinctions between classes seemed to decline. The proliferation of classes ended with very few being especially unique or interesting outside of the role it played within the greater Rifts narrative.

|

| Rogue Scholar: Clearly these books are full of old beer recipes. |

I suspect very few people are interested in playing a game with a class system as presented in Rifts. What it accomplishes in providing a character fixed into the greater story has been easily accomplished by other games, both more simply and more effectively. Instead, the Rifts system ends up becoming nothing more than a horrifying example of bloat within the role-playing world, where the basic ideas of role-playing are pushed aside to get more books on the shelf. Its few strengths are readily outmatched by the absurdity of its weakness, making a framework few should attempt to emulate.

The Elements of a Classy RPG: Introduction

|

| My class is Wizard. Or Magic-User. Or Illusionist. Or Enchanter. |

I thought I would start considering how class is treated in different systems and write a thing or two about it. From there, I hoped to think about what class could mean and, in the context of the new Dungeons & Dragons, what I think it should mean. That being said, when I began this project, it was intended to be a single article. Quickly, it grew into two. From there, I realized that nobody really wants to read a 10,000 word treatise on class and felt it would best be broken up into individual articles. To begin with, I have decided to examine various games, both tabletop, console, and computer, and look at how they handle the concept of class. Specifically, I want to look at what the class encompasses, what it means within the context of the game, how much freedom a character has within that class, and what other features exist to further flesh out a character within that system.

|

| Go ahead and guess what class this is... |

Why look at all of these different systems? The hope is to come to an idea of what the concept of class should entail. A lot of game systems have abandoned the system of class because it is considered far too constraining. Yet, many games continue to employ a class system because it provides a player with a pre-built archetype with which to interact with the game world. On the other hand, some game systems try to make very broad, highly encompassing classes intending to capture every possible permutation that of character that could exist. Although I admit that every rule system is different, the hope is that there is a sort of optimal place for class within a RPG system. Thus, I go on this journey under the assumption that there are a few basic principles that every game should potentially apply to its class system. Whether that is true remains to be seen.

Hopefully, this will be a useful adventure. Although I have read and played a wide variety of game systems, my experience is limited and I hope I can reach all of the relevant different rulesets out there. If there are particular systems worthy of consideration, I hope that readers will recommend them to me so I can consider them further before I conclude. In the history of gaming, it is likely that every reasonable idea has been explored by some game at some point, so hopefully I can find them all with a careful examination of the genre.

Friday, June 8, 2012

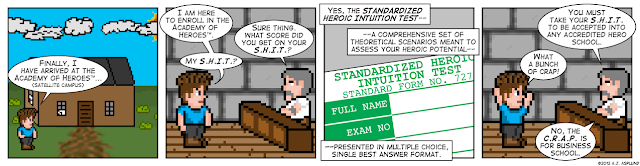

So You Want To Be A Hero? (PWA 1.1)

Phantasy Warrior Advance: So You Want To Be A Hero?

Many years ago, as I started applying to various law schools, I got somewhat frustrated with the process. Granted, after many years in the Navy, I should have been used to it, but it always confounded me how laborious the process for applying to law school is. Even the Law School Admissions Council (LSAC) website, which is meant to streamline all law school applications, felt like an exercise in ridiculous labor.

When I was young, I played the old Sierra game Hero's Quest: So You Want To Be A Hero (later renamed Quest for Glory I: So You Want To Be A Hero). The game was all about you being a recent graduate of the Famous Adventurer's Correspondence School. I never thought much of it until I was older. It seemed like a school for perspective heroes seemed like a funny thing to think about. From that, I started putting together a little comic about it.

I never really know where I go with these things. Making fun of ridiculous acronyms is generally worth a good laugh and I always liked how people go out of their way to name things such that the acronym is entertaining. I've seen a fair amount of it in both the Navy and law.

Thursday, June 7, 2012

Fallout D&D: The Capitol Wasteland

So, as I was thinking of a title for this post, I almost wanted to call it "Gamma World: The Capitol Wasteland" but this character is most distinctly a D&D4E character and not one made under the Gamma World ruleset, so I decided against it.

When I crafted Anakin Skywalker, I had this idea of making an off-stat D&D character. Later, I would repeat that effort with C-3PO. Both of them were characters who were Strength based but neither of them utilized Strength at all based on peculiar power or feat selection. In doing all that, one completely obvious thing seemed to slip right by me.

A Bow Slayer is RIDICULOUS.

I think I experimented with the Bow Slayer at first but was turned off by the fact that Power Strike was for melee weapon attacks only. After doing some reading and thinking, I quickly realized that it did not matter for the Bow Slayer because he was doing an extra +2 or +3 damage with every attack, making the bonus [W] from Power Strike not worth it.

After toying around, I came up with a Bow Slayer idea that worked. Although I have a few Star Wars themed ones sitting in the hopper, I wanted to give people something from a completely different intellectual property for a change.

Fallout 3 is an interesting setting because there are a number of readily portable characters for use in D&D. Furthermore, the existence of Gamma World provides a host of readily transferrable game content (maps, monsters, and the like). Before Gamma World was announced, I had spent considerable time planning a Fallout: Seattle based game; that was, of course, until I learned that Gamma World was a little bit different than I had expected.

There is not a whole lot of strangeness going on with this character. I did do a few things, though, based on the character I was trying to make. I eliminated his Power Strike from the card completely. As I had given him no melee attacks, having power strike on there was pointless. The observant will notice that Charon has a peculiar ability, "Never Dying." This was an attempt to make the Revenant ability "Undying Vitality" work in a more power-based way. I realize some people may be bothered by this. I just feel like it is very easy to forget things written in the "Features" section of the character sheet that have specific triggers or conditions. Hopefully, this will allow people to remember it more easily.

Fallout purists may get upset. Charon is listed as having a chinese assault rifle. That's a personal preference. I eventually gave Charon a chinese assault rifle and 5.56mm ammunition as I felt his special shotgun just was not doing it for me. Also, as it ends up, it worked better for the character concept.

When I crafted Anakin Skywalker, I had this idea of making an off-stat D&D character. Later, I would repeat that effort with C-3PO. Both of them were characters who were Strength based but neither of them utilized Strength at all based on peculiar power or feat selection. In doing all that, one completely obvious thing seemed to slip right by me.

A Bow Slayer is RIDICULOUS.

I think I experimented with the Bow Slayer at first but was turned off by the fact that Power Strike was for melee weapon attacks only. After doing some reading and thinking, I quickly realized that it did not matter for the Bow Slayer because he was doing an extra +2 or +3 damage with every attack, making the bonus [W] from Power Strike not worth it.

After toying around, I came up with a Bow Slayer idea that worked. Although I have a few Star Wars themed ones sitting in the hopper, I wanted to give people something from a completely different intellectual property for a change.

|

| He who controls his contract controls Charon. |

|

| Nice thing about Essentials: more compact card. |