My problem with alignment comes when people disagree on what is good, evil, or otherwise. If the game is not morally ambiguous enough to raise the question, then you don't need alignment. If it is morally ambiguous enough, then the alignment system is more burdensome than not.

Of course, this is just my current viewpoint on the issue. As I thought of it, I thought it would be important to explain my stance on this a little bit better.

Alignment through the Ages

|

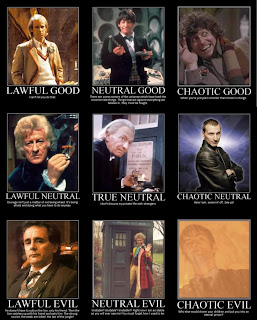

| There are many different versions of the alignment chart but I went for this one. |

In one context, alignment gives every character a sort of quick summary of a character's moral compass. Does she abide by the law whenever possible, or is she a free spirit? Does she put the needs of others before her own, or is she selfish to the core? For decades, players in AD&D have had the pleasure (or frustration) of pinning their character on the nine-point alignment chart.

Of course, how alignment applies to a character depends a great deal on the ruleset and the players. In the Third Edition, alignment was considered a guideline for how a character views the world. "Alignment is a tool for developing your character’s identity. It is not a straitjacket for restricting your character." Hypertext d20 SRD, Alignment. The rules even go further, stating that two characters of the same alignment can have very different perspectives.

The modern rendition of AD&D (First Edition) captured in the Old School Reference and Index Compilation (OSRIC) has a more firm stance on alignment. "Alignment is more than a philosophy; evil and good are palpably real in the game world." OSRIC, pg 42. It is a bit heavier handed than the presentation given in the Third Edition, but there are generally no particular consequences given for characters that deviate from their chosen alignment. To that end, it's primary purpose is to provide a guideline for character roleplay.

As simply a guideline for roleplaying, alignment does not present any major issues because it is a wide field. "Each alignment represents a broad range of personality types or personal philosophies, so two characters of the same alignment can still be quite different from each other." Hypertext d20 SRD, Alignment. If one person things interprets "Good" to have one meaning while another interprets it to mean another, it does not really matter because at the end of the day alignment has no in-game ramification. Alignment does not create any issues in this context because it does not matter.

Where Alignment Matters: The Paladin's Dilemma

Older editions of Dungeons & Dragons have a few situations where alignment does make a big deal. There are a number of iconic examples, such as spells that detect specific alignments or deal extra damage to specific alignments, but many of the best examples come from a single source: the Paladin. From abilities that specifically target evil to the restriction of not being able to associate with characters of Evil alignment, the Paladin is replete with alignment-heavy concerns.

The best example is that of the Paladin's alignment restriction. The holy warrior has the restriction that he be of Lawful Good alignment. "A paladin is a paragon of righteousness sworn to be, and always to remain, Lawful Good. If this vow is ever breached, the paladin must atone and perform penance to be decided by a powerful NPC cleric of the same alignment—unless the breach was intentional, in which case the paladin instantly loses his or her enhanced status as a paladin and may never regain it." OSRIC, p34. Suddenly, what constitutes Good or Evil is fundamentally important and not just a matter of roleplaying. Was that act Good enough, or does Sir Paladin suddenly become Sir Fighter?

There are plenty of iconic examples of "Which is the Good choice?" in the Dungeons & Dragons community. Many a message board post has been spent debating the moral value of saving orc children in a nursery or killing people overcome by evil curses. What is a Paladin to do when faced with these difficult moral choices? Which is the Good and which is the Evil? Or, perhaps, are they all different shades of grey?

I have found that a lot of players do not want to have this debate at the game table. It can often be a personal discussion, as most players will base their decision on their own personal views. As a former student of philosophy, I actually appreciate moral dilemmas. I like the idea that a player would be concerned about the ramifications of his character's actions beyond that of "did it get me more XP?"

As both a player and DM, I find it easier to consider the Paladin's Dilemma in the context of the Paladin's vows and the concerns of his god instead of an arbitrary alignment. The choice of a Dwarf Paladin of Moradin regarding orc babies would likely differ greatly than that of a Human Paladin of Ilmater. Despite that both Paladins are Good servants of Good gods, it is likely that they will choose opposed actions. Neither case really focused on the concept of Good as much as it did the views of each respective god.

But Does Alignment Matter?

It is interesting to me to contrast these two different perspectives on alignment in-game. On one hand, alignment does not really matter because its merely a guide to role-playing. Furthermore, there is a great deal of flexibility within each specific alignment, so a player has a lot of latitude in playing to his character's alignment. This is the simple way to address alignment. Each player is simply using the words to his or her best understanding but that those words have no meaning outside of a player's mind. It seems to me that in this context, it would be just as fair to say your alignment is "Awesome Nice" as it would be to say "Neutral Good." If alignment is going to have such expansive definitions and no ramifications, it actually serves no purpose.

On the other hand, where specific game effects are tied to alignment and require explanation, it can become difficult. Did the Paladin maintain his Lawful Good values? Did the Monk maintain a Lawful perspective? Was the Assassin sufficiently Evil? What choices constitute the Good choices? In these kind of situations, such as the question of the orc babies, alignment suddenly feels more burdensome to play than anything. Spending time questioning the moral value of choices within the context of specific alignments can be difficult, frustrating, or even game-breaking. Usually, the best answers involve disregarding the Alignment system and considering a character's faith, belief, or social history. If alignment is going to have such constrained yet nebulous function as to require leaving it behind in favor of alternatives, it actually serves no purpose.

There are other ways to get around the issue that can be satisfying and entertaining. I have heard of at least one group where the Paladin decided how his actions fell on the alignment spectrum, allowing him some measure of control over the narrative. Of course, if that's the solution, it sounds like that group has essentially disregarded the alignment system in favor of an alternative. Some groups have adopted a belief system comparable to the Mouseguard RPG. The Distinction system used in the Cortex Plus ruleset (comparable to the Fate system's Aspects) is another interesting way to promote role-playing.

There are many interesting ways to find motivations for your character and help promote role-playing. Although the classic D&D alignment system is a way to do it, I reiterate my original statement regarding alignment:

As simply a guideline for roleplaying, alignment does not present any major issues because it is a wide field. "Each alignment represents a broad range of personality types or personal philosophies, so two characters of the same alignment can still be quite different from each other." Hypertext d20 SRD, Alignment. If one person things interprets "Good" to have one meaning while another interprets it to mean another, it does not really matter because at the end of the day alignment has no in-game ramification. Alignment does not create any issues in this context because it does not matter.

Where Alignment Matters: The Paladin's Dilemma

Older editions of Dungeons & Dragons have a few situations where alignment does make a big deal. There are a number of iconic examples, such as spells that detect specific alignments or deal extra damage to specific alignments, but many of the best examples come from a single source: the Paladin. From abilities that specifically target evil to the restriction of not being able to associate with characters of Evil alignment, the Paladin is replete with alignment-heavy concerns.

|

| Who would have guessed such an iconic class would have so many problems? |

There are plenty of iconic examples of "Which is the Good choice?" in the Dungeons & Dragons community. Many a message board post has been spent debating the moral value of saving orc children in a nursery or killing people overcome by evil curses. What is a Paladin to do when faced with these difficult moral choices? Which is the Good and which is the Evil? Or, perhaps, are they all different shades of grey?

|

| What is a Paladin to do in this situation? |

As both a player and DM, I find it easier to consider the Paladin's Dilemma in the context of the Paladin's vows and the concerns of his god instead of an arbitrary alignment. The choice of a Dwarf Paladin of Moradin regarding orc babies would likely differ greatly than that of a Human Paladin of Ilmater. Despite that both Paladins are Good servants of Good gods, it is likely that they will choose opposed actions. Neither case really focused on the concept of Good as much as it did the views of each respective god.

But Does Alignment Matter?

It is interesting to me to contrast these two different perspectives on alignment in-game. On one hand, alignment does not really matter because its merely a guide to role-playing. Furthermore, there is a great deal of flexibility within each specific alignment, so a player has a lot of latitude in playing to his character's alignment. This is the simple way to address alignment. Each player is simply using the words to his or her best understanding but that those words have no meaning outside of a player's mind. It seems to me that in this context, it would be just as fair to say your alignment is "Awesome Nice" as it would be to say "Neutral Good." If alignment is going to have such expansive definitions and no ramifications, it actually serves no purpose.

On the other hand, where specific game effects are tied to alignment and require explanation, it can become difficult. Did the Paladin maintain his Lawful Good values? Did the Monk maintain a Lawful perspective? Was the Assassin sufficiently Evil? What choices constitute the Good choices? In these kind of situations, such as the question of the orc babies, alignment suddenly feels more burdensome to play than anything. Spending time questioning the moral value of choices within the context of specific alignments can be difficult, frustrating, or even game-breaking. Usually, the best answers involve disregarding the Alignment system and considering a character's faith, belief, or social history. If alignment is going to have such constrained yet nebulous function as to require leaving it behind in favor of alternatives, it actually serves no purpose.

|

| The Ultimate Alignment Chart. |

There are many interesting ways to find motivations for your character and help promote role-playing. Although the classic D&D alignment system is a way to do it, I reiterate my original statement regarding alignment:

My problem with alignment comes when people disagree on what is good, evil, or otherwise. If the game is not morally ambiguous enough to raise the question, then you don't need alignment. If it is morally ambiguous enough, then the alignment system is more burdensome than not.But now I ask the question: How has alignment served at your game table? Is it something that people disregard or do players strictly adhere to their alignment? Do questions of alignment come up, or are issues of alignment not the kind of thing your group cares about?

At my tables alignment has served primarily as a way for one participant to block or manipulate the choices of other participants. The rules don't require this, but they can be seen as implying it heavily and for whatever reason it is now firmly associated with alignment, to the point that I think any potential usefulness fruition alignment is irretrievable.

ReplyDeleteI had forgotten old discussions like that from my younger days. "You wouldn't do that, you're Neutral Good!" It's an interesting potentiality of the system and clearly why the Third Edition included the language that it did (about alignment not being a straitjacket).

Delete