The Origin of the OGL

The Open Game License was first given life during the creation of the Third Edition of Dungeons & Dragons. Built on the idea of the GPL (GNU's General Public License), Wizards of the Coast intended to create a sort of generic version of the new ruleset, dubbed the d20 System, and allow third parties to create content for that system that is compatible with Dungeons & Dragons. Ryan Dancey, one of the (former) WotC employees who motivated the OGL, spoke to the overall intent of the license:

|

| The Trademark. |

The net result is that D20 becomes a rosetta stone for making products that will be compatible with Dungeons & Dragons, without requiring us to issue a blanket license for the D&D trademarks. In other words, we want to use the trademarks of D&D to hold the value of the business, rather than the rules themselves.In this way, Wizards of the Coast would make a remarkable change from previous legal stances regarding Dungeons & Dragons and the law. TSR, Inc. had a reputation for threatening lawsuits against people releasing D&D adventures, modules, or other content without a proper license. The OGL as presented to the public seemed to be a very public way to change the relationship between the owners of D&D and the larger community. Like the GPL, the OGL was intended to make the d20 System the Open Source of the tabletop RPG world.

A Tale of Two Types of Content

Wizards of the Coast provided the Open Game License, version 1.0a, for anybody to utilize in their product. Although it contains a significant amount of legal language, an important part of the license is the first paragraph. The license differentiates between two types of content in role-playing games: Open Game Content and Product Identity content. Generally, the creator of content allows other parties to utilize Open Game Content while Product Identity elements remain protected and controlled. Knowing what falls within each type of content is important to knowing what the OGL does and does not do for content creators.

Product Identity is simple enough of an idea to make it worth discussing first. The OGL uses quite a lot of language to describe PI but it can be more readily summarized as creative expressions, such as characters, stories, and other creative content protected by copyright or trademark. From a legal perspective, Product Identity is not terribly interesting because its essentially just copyrighted content and the OGL does not allow third parties to utilize that content. However, contrast the idea of Product Identity with that of Open Game Content (OGC).

"Open Game Content" means the game mechanic and includes the methods, procedures, processes and routines to the extent such content does not embody the Product Identity and is an enhancement over the prior art and any additional content clearly identified as Open Game Content by the Contributor, and means any work covered by this License, including translations and derivative works under copyright law, but specifically excludes Product Identity.

|

| This important process is what the OGL is all about sharing, right? |

In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.17 USC §102(b). The definition of OGC also includes some suspicious patent language, such as referencing a specific embodiment or prior art. Perhaps, a better way to describe OGC is to say it includes all of the content that does not fall under copyright or trademark protection, including any patentable content, and anything else specified by the creator.

Given all this, it may be helpful to describe Open Game Content and Product Identity a little bit differently. Product Identity is specifically content protected by copyright and trademark while Open Game Content is specifically content that is legally unprotectable or protectable via a patent.

License to Breathe

Perhaps the most interesting aspect about the OGL is the fact that a majority of the content that the license gives permission to use (the Open Game Content) is content that the creator had no legal control over to begin with. As noted podcast Law of the Geek described it, the OGL was a license to breathe. The permissions granted over Open Game Content was no more a grant than had existed without the OGL. If that is the case, what's the point of the OGL?

If somebody were to devise the rules to a role-playing game system and patent it, the OGL would be a way for them to retain their legal protection while allowing third parties to publish content in compliance with the license. Of course, patenting rules to a game has its own share of problems and thats why its rarely ever done. After a brief search through Google Patents, I cannot find anything that could be interpreted as a role-playing game. So, if nobody is patenting the rules to a role-playing game, why the OGL? Simple answer: TSR, Inc.

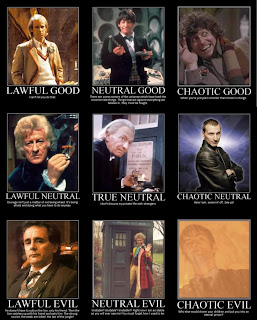

|

| This is why people *think* we need the OGL. |

TSR, Inc. had a long history of trying trying to protect the D&D line through licensing agreements, trademark disputes, and other legal action. The earliest example comes from a licensing agreement between TSR and a company called Judges Guild. Judges Guild was, for all intents and purposes, the first company to conceive of writing and publishing adventure modules for the D&D game. Founded by a man named Bob Bledsaw in 1976, he specifically went to TSR to seek some sort of agreed license to publish this kind of content. They agreed and the license remained in place until 1982, the point that TSR realized there was money to be made in adventure content and they cancelled the license.

Only a few years after Judges Guild, TSR had a new upstart competitor by the name of Mayfair Games. Founded by an attorney named Darwin Bromley, one of Mayfair's earliest products was a series of AD&D adventures known as Role Aids. Within two years, TSR was already threatening legal action against Mayfair. The result from that dispute was the 1984 trademark agreement, an agreement between Mayfair and TSR that allowed Mayfair to utilize the TSR and D&D trademarks in a limited fashion. The important element in this potential suit and future agreement was that it centered around trademark use and infringement. Nothing here concerned rules, game systems, or the like.

|

| This is what it looks like to publish a product for AD&D without a license or OGL. |

The Concession that is the OGL

When Wizards of the Coast created the OGL in 2000, it did a strange thing. The owner of Dungeons & Dragons was saying to the world, "We will allow you to utilize this game system as long as you abide by this simple, harmless license. We concede." From that concession came the Year of d20. New companies, new imprints, and many new products continued to appear on game store shelves. From what can be seen, the OGL ushered in a new era of Dungeons & Dragons.

Despite this era of good feelings, the reality is that the concession that was the OGL was really no concession at all. The OGL granted no rights or privileges to third party publishers that they did not already have. TSR's history of legal action never focused on the rules of the games or copyright issues but instead on trademark infringement/confusion. WotC did not give up any legitimate legal rights or protections when they allowed the world to publish under the OGL. [Note: They did agree not to bring suit against licensees, but since the suit would be without merit, that is not much of a right to surrender.] The OGL only became the backbone of the modern RPG community because Wizards of the Coast (specifically, Ryan Dancey) convinced the RPG community that it was the best idea.

Conclusion

This brings up the question: what's the point of the OGL? At this point, the OGL is a relevant issue in the modern tabletop RPG community because people think it is necessary. Mutants and Masterminds could have existed without the OGL. Pathfinder could have existed without the OGL. Fate could have existed without the OGL. 13th Age could have existed without the OGL. All the OGL did was let people know that they could do the things they could already do.

Does the tabletop RPG community need the OGL? Probably not. Like several legal minds have said, it's nothing more than a license to breathe. But, for a community that thought it could not breathe without permission, the OGL serves an important purpose. It let's the gaming community feel safe about publishing game content, something that has had a long history of being a quasi-dangerous game.

The statements made in this article are the opinions of the author (and the author alone) and do not constitute legal advice. Comments posted on this article do not create an attorney-client relationship. Much of the historical information in this post come from a series of articles written by Shannon Appelcline. For additional historical information, look for his upcoming four volume work Designers & Dragons, coming in 2013.